The Best GDB Tutorial In The World

This article is for developers who have used a debugger before (GUI or command line), thus you are familiar with debugging concepts/terminology like “attaching”, “breaking”, “continuing”, “stepping” etc. What we’ll focus on is how to get GDB to do that stuff - as well as how to use some of the cooler features of GDB (such as automated debugging).

- broken - When I say things like “the process is broken”, I don’t mean “not working”, I mean the process is stopped (by the debugger).

GDB is a command line C/C++ debugger1.

Launching

There are a couple of ways to launch GDB. We’ll go through the most useful ones.

- To launch gdb and attach it to an already running process:

gdb -p <process_id>The process will be broken as soon as gdb attaches to it. You will see the gdb prompt, which looks like this:

(gdb). Anytime you see the gdb prompt in your terminal, you can type in gdb commands. Gdb commands can do things like set breakpoints, examine callstack, examine variables, etc. - To launch gdb, then have gdb launch an executable:

- Specify the executable when launching gdb:

gdb <executable_file> - Type the gdb command

runto launch the actual executable. If you would like to pass any arguments to the executable before it is launched, simply concatenate them to theruncommand, like so:run arg1 arg2 arg3.

- Specify the executable when launching gdb:

Once your process is running, you can force it to break where ever it is at, by hitting ctr + c when the gdb terminal is focused.

GDB is really only useful for debugging programs that were compiled with the

-gflag. The-gflag tells the compiler to include information in the binary that maps lines of source code to area in binary.

gdb -p <pid>to attach gdb to an existing processgdb <exe_file>to launch gdb and prepare it to launch a new process from an executable filerunto start the executable filerun [arg1] [arg2] [arg3...]to start the executable file with specified command line arguments

Execution Control

Here are some GDB commands that control the execution of your process.

continueto continue running the process until it hits a break pointnextto execute one line of codestepto step into the next functionfinishto run until the current function finishes

Remember, you can press ctr + c (while the GDB terminal window is focused) to break your process.

Viewing Source

While your process is broken (or at some other time), you may want to have a look at some source code.

As soon as your process breaks, your “source code” pointer points to the line of code that your process was about to execute before it broke. If you type list, you will be shown 10 lines of source code around your “source code” pointer, then the pointer will get incremented. So if you type list again you’ll see the next 10 lines of code in the same file. The more you type list, the “further down” the file you go. Type list - (notice the -) to go back up 10 lines. So typing list will move you down the file while list - will move you up.

You also have the option of viewing the source code for a particular function. Type list <file_name>:<function_name> to show 10 lines of code from a particular function in a particular file. Two notes on this:

- If you have two files with the same name, then

<file_name>needs to include the name of the folders that they are in. If those folders have the same name, then you need to include the name of the folders that those folders are in. Basically include as much of the path as you need to disambiguate between the two files! <function_name>needs to be the name of the function exactly as you would specify it in C/C++. Here are some examples:myFunctionMyClass::myFunctionMyClass::myOverloadFunction(int,int)- when you have two functions with the same name, you can disambiguate by including argument types

You can also just do list <function_name> (leaving out the file portion), as long as the <function_name> is the fully scoped function name, and there is no ambiguity.

Note that after you view the source code for a particular function, your “source code” pointer now points here. So subsequent list and list - commands move you from here.

One really useful thing is the info functions [regex] command. It shows you the fully scoped name of all the functions that have been compiled in the binary modules of the executable, filtered by a regular expression. For example, info functions '[bc]ool' will show you the fully scoped name of functions that have bool or cool in their name. You often have a vague idea of a function you’d like to put a breakpoint on, so you use this info functions [regex] command to get the fully scoped name of the function, and then you use the break command to set a break (given the fully scoped name of the function).

Similarly, you can use the info variables [regex] to get the fully scoped name of global/static variables that match a certain regular expression.

listto see next 10 lineslist -to see previous 10 lineslist <file_name>:<function_name>to show source code for a particular functioninfo functions [regex]to get fully scoped name of functions that match a certain regexinfo variables [regex]to get the fully scoped name of global/static variables that match a certain regex

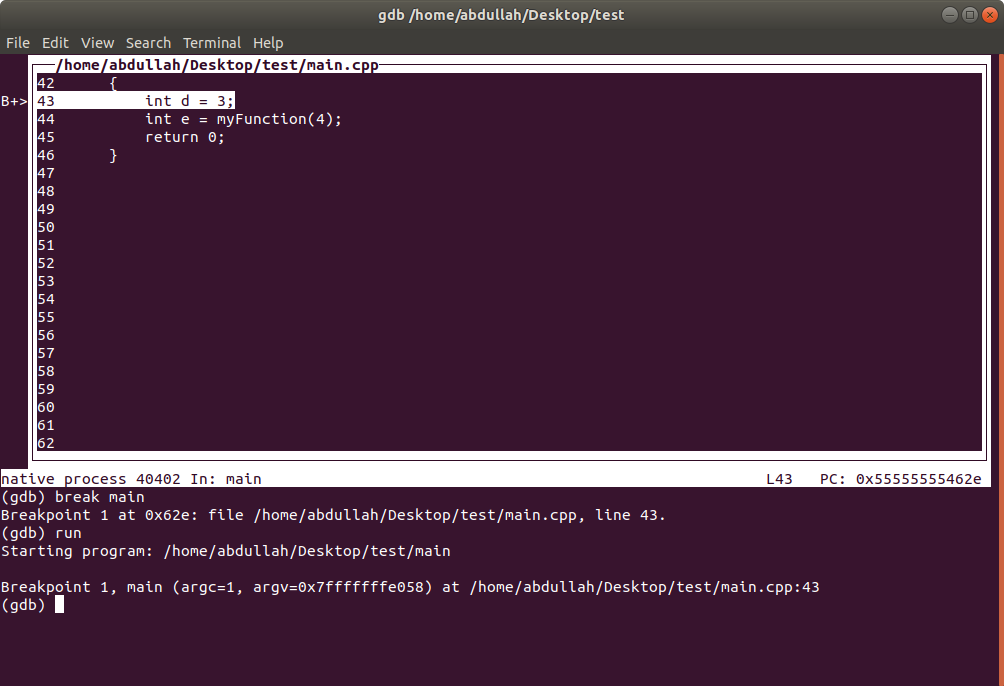

Using TUI

The easiest way to view your source as you step through a program is to enable TUI (Text User Interface) mode. To enable TUI mode, type layout next. Here is what you’ll see:

As you step through (using commands like next and step), you’ll see that the highlighted line of code will change.

Type tui disable to go back into terminal mode.

layout nextto enter TUI mode,tui disableto exit TUI mode

Viewing Variables

print <variable_name> to print the contents of a variable (of course, the variable must be in scope when this is called)

Examining Call Stack

backtracecommand is used for printing the call stack. If the call stack is a bit too big, you can print the top, for example, 5 frames by doingbacktrace 5.- you can “select” a frame (function) in the call stack by doing, for example

frame 3(select the 3rd frame from the top)- remember by default the “selected frame” is the top frame (i.e. the function that you broke in)

info argscan be used to view the value for all arguments passed to the current function (i.e. the current frame)info localscan be used to view the values for all local variables in the selected frameupanddowncan be used to select the next frame up or down

Break Points

Here are some GDB commands for setting, viewing, enabling/disabling, and removing break points.

info breakpointsto view a list of break points you’ve set- will show you the unique number associated with each break point

- will also show you whether the break point is enabled, where (what function) the break point is in, and how many times its been hit so far

break <function_name>to set a break point on a particular function- the syntax for specifying function follows the same rules discussed in “Viewing Source” section above

delete <break_point_number>to delete a break pointdisable <break_point_number>to disable a break point- disabling makes the break point un-hittable, but it will still show up when you do

info breakpoints - sometimes quickly enabling/disabling a break point is desired rather than completely deleting it

- disabling makes the break point un-hittable, but it will still show up when you do

enable <break_point_number>to enable a break point

Conditional Break Points

You can make break points conditional (i.e. they should only trigger when a certain condition is true). The syntax to creating a conditional break point is break <function_name> if <condition>. The <condition> is any valid C++ expression. If it evaluates to true or any non 0 number, the condition is fulfilled.

You can modify the condition of an existing breakpoint by doing condition <break_point_number> <condition> (even if the break point doesn’t currently have a condition, this syntax will add one). If you just do condition <break_point_number> (i.e. no condition specified), it’ll remove the condition of the break point.

You can use convenience variables in conditions.

Auto Execute Commands When Hit

You can have gdb automatically execute a bunch of gdb commands when a particular break point (break point 2 in this case) hits. Here’s how to do it:

commands 2

print "hi there"

continue

end

What we’re doing above:

commands 2specifies that when breakpoint2is hit, we want to execute some commands- every line that follows until

endis the list of commands that will be executed when break point 2 is hit- so we are telling gdb, that when break point 2 is hit, print

hi thereand then continue execution (i.e. don’t stop the process)

- so we are telling gdb, that when break point 2 is hit, print

To remove auto executed commands from a breakpoint (from break point 2 in this case) just do:

commands 2

end

In other words, just put end without any specifying any commands.

This is an extremely useful feature, especially considering the fact that gdb commands support control flow statements (if/while), and you can set gdb convenience variables.

Catch Points

Catch points are similar to break points, except that they stop the process when a certain event occurs. The event can be things like the process receiving a particular signal or throwing a particular exception.

To break when the process throws a particular exception:

catch throw [regex]

Whenever the process throws an exception whose name matches the supplied regex, it will be broken. Notice, the regex is optional, if you leave it out, then the process will be broken when it throws any exception.

To break when the process catches an exception:

catch catch [regex]

That’s right, it’s

catch catch(twice). This isn’t a typo.

Whenever the process catches an exception whose name matches the supplied regex, it will be broken. Again, notice the regex is optional, if you leave it out, the process will be broken if it catches any exceptions.

To break when the process receives a particular signal:

catch signal SIGINT

In the above case, we break the process when it receives SIGINT.

To break the process when it receives any signal:

catch signal all

Here are some other events you can catch:

catch forkbreaks the process when it callsfork()catch load [regex]breaks the process when it loads a particular shared library (dll)- if you want to break when any dll is loaded, leave out the regex

catch unload [regex]break when unloading dlls. Leave out the regex if you want to break when any dll is unloadedcatch syscall [sys call name]break when the process calls a particular system call

Like break points, catch points can have conditions and automatically execute commands when hit. The syntax for these things is the same as for break points. Also, info breakpoints will show you the catch points you’ve placed as well.

catch throw [regex]to break when a particular exception is throwncatch catch [regex]to break when a particular exception is caughtcatch signal SIGINTto break whenSIGINTis received (replace SIGINT with any signal you want)catch signal allto break when any signal is received- catch points, like break points, support 1) conditions and 2) automatically executing gdb commands when hit

info breakpointswill show you your catch points too

Watch Points

You can have your process break when a certain piece of global/static data is read and/or written to. First, find the name of the data (variable). You can use the info variables [regex] command to search for variable names. Once you know the name of the variable of interest, just do watch <variable name>. This will place a “write” watchpoint, which means that whenever the variable is written to, your process will break.

If you just want to break when the variable is read, do rwatch <variable name>, and if you want to break when the variable is read or written, do awatch <variable name>.

info breakpoints will show watchpoints too.

Cool GDB Features

Automating

You can tell gdb to automatically start executing gdb commands from a file once it launches.

First put your gdb commands in a file (the extension doesn’t matter).

print "i'm starting"

break SomeClass::someFunction

continue

# more gdb commands here...

Then start gdb like this:

gdb --batch -x <my_command_file> --args <executable_name> arg1 arg2 arg3

This tells gdb to launch a particular executable (<executable_name>), and then start executing gdb commands from a particular file <my_command_file>.

Convenience Variables

GDB can store some information in variables as you are debugging. To store the number 5 in a variable called $my_var do set $my_var = 5. You can also set strings, e.g. set $my_string_var = "hello".

Remember the print command? You can use it to print the content of convenience variables as well, like so: print $my_var.

Notice that convenience variables start with $.

Control Flow Statements

GDB has support for control flow constructs like if and while statements. These are useful because remember, you can write your gdb commands in a file and then tell gdb to execute the commands in that file.

Syntax for if:

if <condition>

...gdb commands here...

...more gdb commands...

end

Syntax for while:

while <condition>

...gdb commands here...

...more gdb commands...

end

Remember, you can use use convenience variables in conditions :).

Shell Commands

You can execute any shell command by prepending it with !. For example, !clear will clear your terminal. When gdb gets a command prepended with !, it will just send it to the shell interpreter.

Puttin It Together

When you put the following together:

- convenience variables

- conditional break points

- auto executing commands when a break point is hit

- executing gdb commands from a file upon launch

- if/while constructs

- being able to run arbitrary shell commands as long as you prepend them with

!

It doesn’t take a creative genius to instantly realize the immense amount of power here.

For example, what if I want to:

- launch my program

- attach gdb to it

- put a break point on a particular function (say

myFunction()) - count how many times that function gets hit

- if it gets hit more than 5 times, start a completely separate program, and then quit debugging

Here is a gdb script that will do all of that

# initialize hit counter to 0

set $hit_counter = 0

# put break point on function

break myFunction

# - make break point track how many times it's been hit

# - if it gets hit enough, start another program, then exit

commands 1

set $hit_counter = $hit_counter + 1

if $hit_counter >= 5

!my_other_program

quit

end

continue

And you’d start GDB like this:

gdb --batch -x <my_command_file> --args <executable_name> arg1 arg2 arg3

With a little bit of ingenuity and creativity, you can do some very powerful stuff that can save you some serious manual debugging time!

Going Back in Time

GDB allows you to run your program backwards. To use this feature, after you attach gdb to a process, type record. This will make it so that gdb starts recording the execution of your program. By recording, it is able to play things backwards (effectively turning time back). Then use the command reverse-continue to make your process execute backwards until it hits a breakpoint (or a catchpoint, or a watchpoint).

You can also use commands like reverse-step and reverse-next. reverse-next will run your program one line backward in time. reverse-step will run your program backwards, stepping into (the bottom of) any functions on the way (just like the regular step command).

When you want GDB to stop recording execution, type record stop. Recording execution will slow your process down, so keep that in mind.

recordto start recording execution (execution must be recorded in order to use reverse debugging)reverse-continueto run backwards until you hit a breakpoint (or catchpoint/watchpoint)reverse-nextto run backwards just one line upreverse-stepto run backwards, stepping into the next function (well, the bottom of it)record stopto stop recording execution

Quiting

When running gdb in interactive mode (i.e. you didn’t start it by telling it to execute commands from a command file), do quit then y to confirm.

If you are not in interactive mode, just quit is enough.

Footnotes

-

I know that GDB can debug a few other languages (like Fortran), but I want to focus on C/C++. ↩